As the last remaining house was torn down in a postwar makeshift residential district near the center of Sendai, it marked the end of an era for those who had come to call the neighborhood their home.

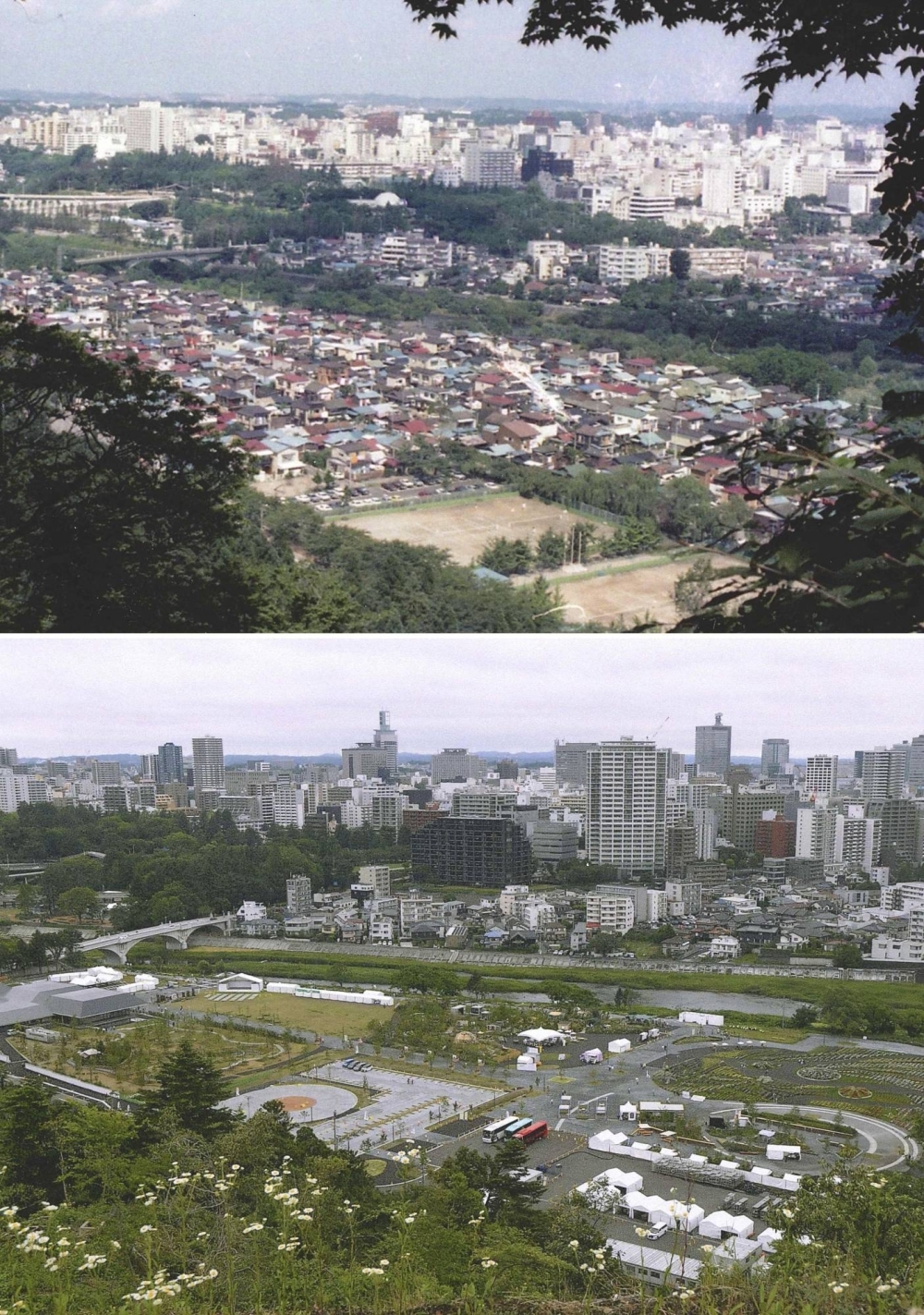

Despite many wishing to stay in the Oimawashi district, residents were asked to vacate their houses to make way for a greenery project as the city of about 1.1 million moved to demolish what was seen as a symbolic relic of its administration in the immediate post-World War II period.

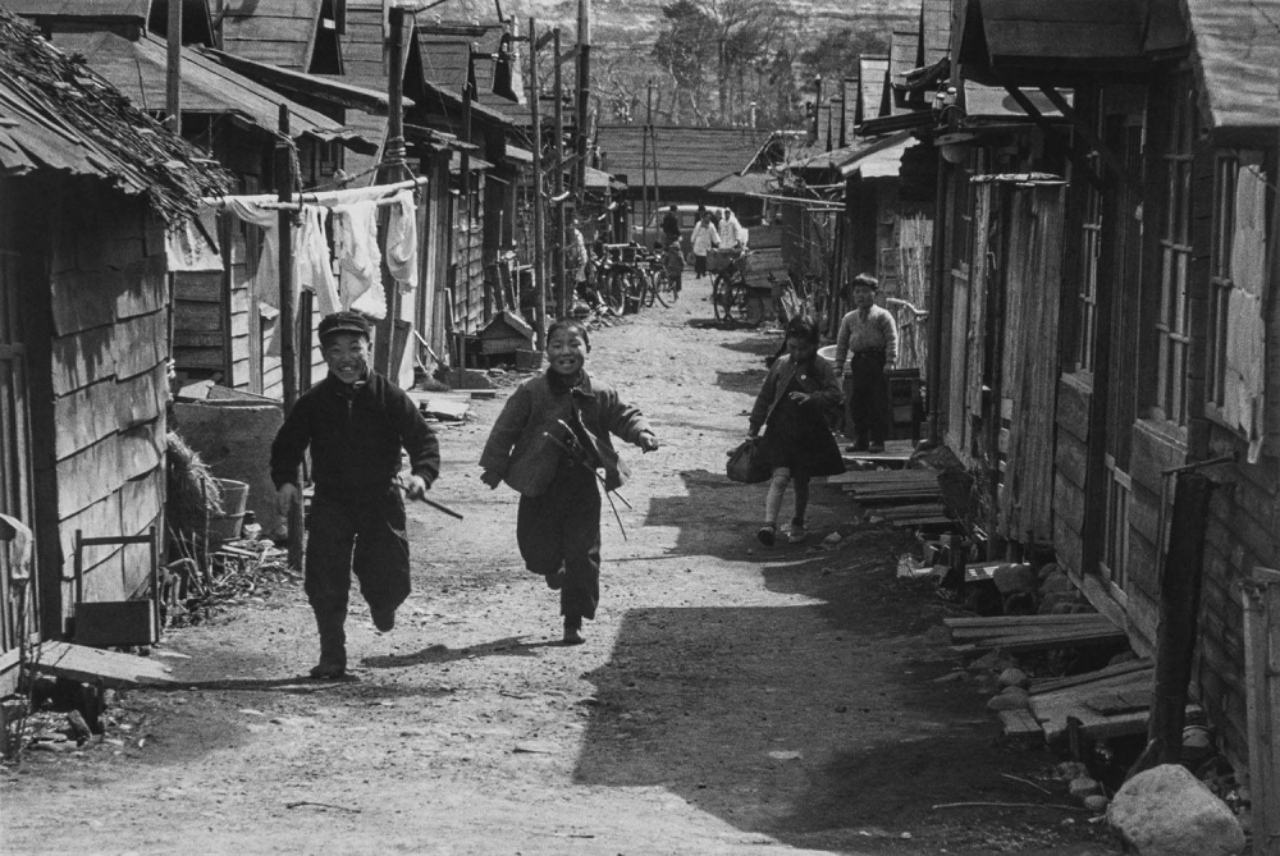

The district was built nearly 80 years ago for people whose property had been destroyed by bombing in the war, meaning despite its dilapidated infrastructure, many considered the neighborhood a place of refuge.

Hoping to shine a spotlight on the area’s history, Sendai Mediatheque, the city’s public library and cultural hub, has been holding exhibitions, using art to convey the district’s past and the memories of those who lived there.

In 1946, some 620 temporary tenement homes were built in Oimawashi for people to live in on state-owned land between Aobayama, the site of Sendai Castle, and the Hirose River. Those who moved there included air-raid victims and people who had been repatriated to Japan after the war.

Many residents bought their homes and went on to repair or rebuild them, with plans to settle in the district for good. At one point, the population reached around 4,000.

Upon hearing that the city was redeveloping an area that included the Oimawashi settlement into a park, many residents protested, saying they had not been informed about the project in advance or would be asked to vacate their homes.

The situation developed into a standoff, and years passed. The city’s authorities refused to maintain the sewage system and other services necessary for ensuring basic living standards because the evictions would go ahead.

The last resident of Oimawashi was a man in his 60s who lived in the settlement’s only house left standing. He had lived alone, and had been the only person remaining in the settlement since 2019. He eventually agreed to move out in August last year, and the house was demolished in the spring of this year.

The last house stood for 77 years before it was torn down. The rest of the area was converted into a park with a monument to commemorate the district, which now stands quietly as the sole reminder of that time.

“The town has disappeared, with only a stone monument remaining. We thought, ‘Is that it? There should be more.’ The local government has a responsibility for this history,” said Sendai Mediatheque’s artistic director, Kenji Kai, 60, explaining why the initiative for the art exhibition was launched.

Kai commissioned two artists for the exhibition. One was Shun Sasa, 37, a native of Sendai, who often passed by the neighborhood as evictions took place when he was a high school student.

As many of the houses had been demolished by that time, Sasa recalled, “I felt a strangeness about it because the houses that remained were sparsely spread over a huge plot of land.”

Through conducting surveys of the district and interviews with former residents since around 2015, Sasa learned that they had pooled their funds together to pave roads and install water pipes in the absence of adequate government infrastructure.

Living along narrow alleys, they helped each other out and overcame major disasters, such as fires and floods.

Sasa said that his work made him more aware of the vibrant lives lived by people in the district, who were facing extraordinary circumstances.

The exhibition first shows “sketches of the individual memories” of former residents, which includes a timeline of the district and the history of the city and the body that oversaw its self-governance, accompanied by newspaper articles and photographs.

It then takes visitors into a larger space featuring displays of festivals, nature, and nursery school activities that took place in the district.

The exhibition also features the experiences of former residents who lived in the area written down on more than 100 cards, as well as various items and appliances they used such as washing machines and benches.

Among the other items in the exhibition is a video showing the demolition of the last house, and garden lanterns, which were made with the help of residents at a workshop.

The other artist was Nobuaki Date, 59, who made ukuleles from scrap lumber left from demolished temporary housing, sourced mainly from the Kansai region.

“I wanted to put together a myriad of perspectives of the town and get closer to the real image,” Date said. “The proof that people lived there is enriched by the involvement of others,” he added.

While acknowledging that history going back nearly a century could be displayed in chronological order, Sasa said doing so could make it “difficult to display all the raw emotion of the people involved.”

The organizers have been collecting new material from residents, who have been visiting the exhibition that ends on Sunday, documenting their life and times in the community.

“Because it happened this year (when the settlement closed), I think it left a huge impact,” Sasa said.